Discover Miss Rae's Room Dyslexia Blogs, a comprehensive series dedicated to empowering educators and promoting effective strategies for students with Dyslexia. From different types of Dyslexia and Dyslexia screeners to signs of Dyslexia and evidence-based interventions and accommodations in the general education classroom, explore the infusion of the Science of Reading into instruction, explore school's roles in defining Dyslexia, and learn about best practices for teaching students with Dyslexia. Gain valuable insights and practical guidance to create inclusive and supportive learning environments. Start your journey towards improving outcomes for students with Dyslexia today!

|

10/15/2021 1 Comment Structured Literacy: A Comprehensive Approach for Teaching Reading to Students with Learning Disabilities

Unlock the potential of structured literacy! Learn about the evidence-based principles and practices that make structured literacy an essential approach for teaching reading to students with learning disabilities. Discover how this systematic, explicit, and diagnostic instruction fosters reading skills and comprehension. Access a helpful checklist for effective implementation and explore renowned structured literacy programs for optimal results.

Structured Literacy is a research-backed best practice approach that empowers students with learning disabilities to develop foundational literacy skills. With its purposeful, direct, systematic, and explicit framework, structured literacy enables students to decode printed words and engage in meaningful reading experiences. By embracing individualized instruction and informed assessments, this approach offers a blueprint for delivering effective and targeted teaching.

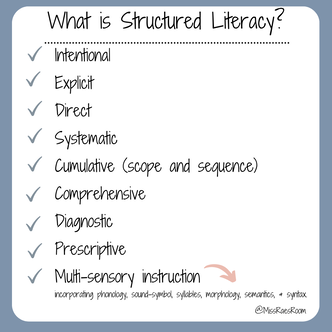

Moreover, structured literacy serves as an umbrella term coined by the International Dyslexia Association (IDA) to unify evidence-based programs and approaches aligned with the Knowledge and Practice Standards. While benefiting all students, structured literacy has proven essential for those identified with Specific Learning Disability (SLD)/Dyslexia. Structured literacy is intentional, explicit and direct, systematic, cumulative (scope and sequence), comprehensive, diagnostic, prescriptive, and multi-sensory instruction, incorporating phonology, sound-symbol, syllables, morphology, semantics, and syntax.

This approach has demonstrated success in teaching all students to read and write (Moats, 2019; Young, 2018). In fact, over 60% of students in general education classrooms can benefit from structured literacy-based instruction (Young, 2018).

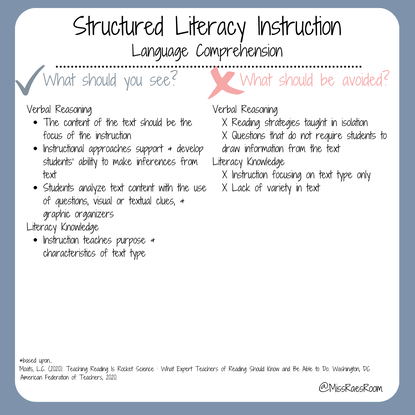

Structured Literacy emphasizes intentional, diagnostic, explicit, and direct instruction that engages students and facilitates progress.

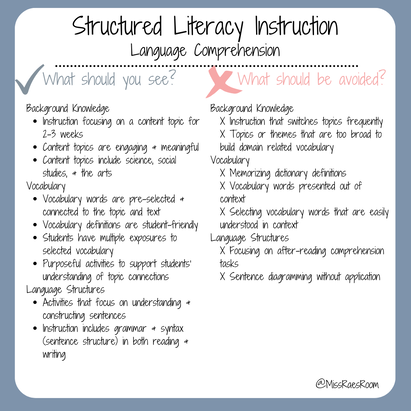

It follows a systematic scope and sequence, gradually introducing language concepts from simpler to more complex, ensuring mastery before advancing. With scaffolded instruction, corrective feedback, and multi-sensory techniques, structured literacy enhances memory and learning by engaging multiple pathways in the brain. This comprehensive approach covers all aspects of language, including phonology, sound-symbol relationships, syllables, morphology, semantics, and syntax.

By integrating these components, students develop a deep understanding of reading and language comprehension.

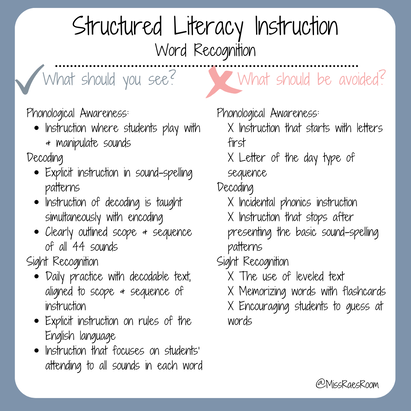

The power of structured literacy lies in its focus on systematic and explicit instruction in word recognition skills. Research confirms that efficient and automatic word recognition plays a pivotal role in reading comprehension. A structured literacy-based curriculum commences with a strong emphasis on phonemic awareness, enabling students to concentrate on the sounds in words. As students progress, they learn advanced skills while acquiring the rules of the English language through aligned instruction in decoding and encoding. Structured Literacy supports the learning of ALL learners, including those with Dyslexia!

Research supports the effectiveness of structured literacy instruction for students at-risk of literacy difficulties (Gersten et al., 2009). Renowned structured literacy programs like Orton-Gillingham, Wilson Reading System, and Lindamood-Bell have proven effective for students with learning disabilities. For instance, Children’s Dyslexia Centers, Inc. provide structured-literacy instruction (Orton-Gillingham) to students free of charge, resulting in significant improvements among struggling readers with dyslexia markers.

Structured literacy ensures explicit and systematic instruction in sound-spelling patterns and spelling, equipping students to accurately and efficiently decode words. By following a clear scope and sequence that attends to all sounds in each word, students can crack the reading code. Explicit and systematic instruction benefits all students, laying the foundation for successful reading development.

To help ensure that you are providing the necessary instruction and support for your students to become successful readers, consider using THIS checklist.

This checklist can serve as a guide to help you implement Structured Literacy principles and practices in your teaching. It is designed to support you in making sure that your instruction is explicit, systematic, and evidence-based, which are the hallmarks of Structured Literacy instruction.

Structured literacy, grounded in the Science of Reading, is a powerful tool for supporting the learning of all students, including those with Dyslexia. Its explicit and systematic approach addresses the language basis of learning disabilities, covering essential elements such as sound-symbol instruction, semantics, and syntax. By following a logical scope and sequence, students progress from foundational to more challenging skills, ensuring mastery at each step. Evidence consistently confirms that explicit, systematic, cumulative, and multisensory instruction is essential for students who struggle with reading, regardless of their background. Early intervention is particularly beneficial, setting students on the path to proficient reading. Unleash the potential of structured literacy and empower students with learning disabilities to become confident readers. By implementing evidence-based strategies, systematic instruction, and targeted interventions, you can transform the reading experience for every student. Join the structured literacy journey and witness the profound impact it has on students' reading abilities. Happy Teaching! Miss Rae

References:

Gersten, R., Compton, D., Connor, C.M., Dimino, J., Santoro, L., Linan-Thompson, S., & Tilly, W.D. (2009). Assisting students struggling with reading: Response to intervention and multi-tier intervention for reading in the primary grades, a practice guide (NCEE 2009-4045). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved from http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/publications/practiceguides/. Kilpatrick, D.A. (2015). Essentials of Assessing, Preventing, and Overcoming Reading Difficulties. Moats, L. (2019). Hard Words: What Teachers Don’t Know About Teaching Reading and What to Do About It. Voyager Sopris Learning, 2019 Spring Webinar Series. Voyager 2019. Young, N. (2018). Ladder of reading infographic: structured literacy helps all students. Retrieved from https://dyslexiaida.org/ladder-of-reading-infographic-structured-literacy-helps-all-students/. Snow, C.E., Burns, M.S., & Griffin, P. (eds.) (1998). Preventing reading difficulties in young children. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. Related Blogs...Related Courses...Related Resources...

1 Comment

Cindy Parks

10/1/2022 04:24:20 pm

This was the most well-written explanation of Structured Literacy that I have read. Thank you!

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed