The Importance of Working Memory in Reading: Classroom Accommodations

The Importance of Working Memory in Reading: Classroom Accommodations

What is Working Memory?

How do we assess a student’s Working Memory?

What are the different types of Working Memory?

Why is Working Memory Important?

What Role Does Working Memory Have in Reading?

How Do You Know What a Student’s Working Memory Ability is Without Testing?

How can we support Working Memory in the classroom?

-Accommodations

-Working Memory Lesson Plans

How can teachers support Working Memory in Reading?

How can teachers support Working Memory skills in Students with Learning Disabilities?

What are IEP goals for Working Memory?

What is Working Memory?

How do we assess a student’s Working Memory?

What are the different types of Working Memory?

Why is Working Memory Important?

What Role Does Working Memory Have in Reading?

How Do You Know What a Student’s Working Memory Ability is Without Testing?

How can we support Working Memory in the classroom?

-Accommodations

-Working Memory Lesson Plans

How can teachers support Working Memory in Reading?

How can teachers support Working Memory skills in Students with Learning Disabilities?

What are IEP goals for Working Memory?

Reading is an essential skill that opens doors to learning and success. But for some students, weak Working Memory can be a major barrier. In this post, we'll explore how teachers can help students overcome challenges with Working Memory!

What is Working Memory?

|

Working Memory refers to our ability to temporarily hold and manipulate information in our minds. It is a crucial component of executive functioning, which involves higher-level cognitive processes like planning, problem-solving, and decision-making.

In the classroom, Working Memory is essential for students to follow multi-step directions, remember and apply information learned in previous lessons, and decode unfamiliar words. It also helps students determine which tasks require the most attention and allocate resources accordingly. When our attention wanes or our memory system gets overloaded, we can lose information stored in Working Memory. This is especially true for students with limited Working Memory capacity. |

How do we assess a student’s Working Memory?

Tests of cognition assess a student’s Working Memory. Tests of Working Memory measure a student's ability to demonstrate attention, concentrate, hold information in their minds and be able to work with it or manipulate it during a short period of time. Students are provided with a series of information and asked to recall the information. The WISC-IV Working Memory Index is one such example of a test of Working Memory.

And when we test a student’s working memory, we want to look at how they are able to perform these tasks both visually and auditorily. This is because there are two types of Working Memory.

And when we test a student’s working memory, we want to look at how they are able to perform these tasks both visually and auditorily. This is because there are two types of Working Memory.

Are there different types of Working Memory?

Yes, there are different types of Working Memory. Two of the most commonly recognized types of Working Memory are Verbal Working Memory and Visual Spatial Working Memory.

Verbal Working Memory is related to language-based information. Students use their Verbal Working Memories in the classroom for remembering verbal instructions and questions or remembering what to say during a turn-taking game. In the area of reading, students use this memory to match sounds to letters, decode, read fluently, and develop reading comprehension.

On the other hand, Visual Spatial Working Memory is connected to information related to locations, pictures, movement, and the physical properties of objects. Students use their Visual Spatial Working Memories for copying information from the whiteboard, sequencing events from timelines or from stories, and keeping their place while reading.

Verbal Working Memory is related to language-based information. Students use their Verbal Working Memories in the classroom for remembering verbal instructions and questions or remembering what to say during a turn-taking game. In the area of reading, students use this memory to match sounds to letters, decode, read fluently, and develop reading comprehension.

On the other hand, Visual Spatial Working Memory is connected to information related to locations, pictures, movement, and the physical properties of objects. Students use their Visual Spatial Working Memories for copying information from the whiteboard, sequencing events from timelines or from stories, and keeping their place while reading.

Why is Working Memory Important?

|

Working Memory is critical for a successful school experience. As adults, we have already acquired much of the knowledge and skills we need to successfully function; however, students are continually being bombarded with new knowledge in multiple content areas all day, every day. They are expected to learn, whether or not they are interested in it, and demonstrate mastery of this newly learned knowledge on a daily and weekly basis. This is the reason why a student’s Working Memory ability is a key predictor of later academic achievement.

|

Working Memory has actually been shown to be a better predictor of long-term academic performance than a student’s IQ because it is the measurement of their potential to learn, rather than what they already know. Students with weak Working Memory ability, as a result, are considered to be at risk for academic underachievement.

What Role Does Working Memory Have in Reading?

The end goal of learning to read is Reading Comprehension. And Working Memory is critical for Reading Comprehension. Working Memory skills are not just required to comprehend what a student has read, though; Working Memory skills are required for every component of reading needed to be able to read a text and comprehend it.

Working Memory skills impact a students’ phonological awareness skills. An example of this is when students are unable to identify rhyming words.

Tell me which words rhyme: cat, dog, rat, mouse

To perform this task, a student must hold those words in their mind, compare all of the words (cat/dog, cat/rat, cat/mouse, dog/rat, dog/mouse, rat/mouse), and then, state aloud the words that rhyme.

Working Memory skills impact a students’ phonological awareness skills. An example of this is when students are unable to identify rhyming words.

Tell me which words rhyme: cat, dog, rat, mouse

To perform this task, a student must hold those words in their mind, compare all of the words (cat/dog, cat/rat, cat/mouse, dog/rat, dog/mouse, rat/mouse), and then, state aloud the words that rhyme.

|

Working Memory is needed to decode unfamiliar words. To decode a word, students must be able to hold the entire sequence of sounds long enough to blend those sounds together and read a word. This can impact a student’s Oral Reading Fluency.

Click HERE to read about Assessing Oral Reading Fluency and HERE to read about the Secret to Teaching Oral Reading Fluency. |

And students must be able to hold each decoded word to connect it within the sequence of a sentence and then, connect those ideas within a text to comprehend it as a whole - or demonstrate reading comprehension.

Working Memory is involved in this comprehension beginning at the word level for students. Once a word is read, its corresponding meaning is identified and held in the student’s mind. Working Memory must then be used for comprehension at the sentence level when a student is then required to keep each of those word meanings in their mind and then, link these to make meaning from the sentence. This task is repeated at the paragraph level, requiring Working Memory once again. Students with strong decoding skills, but weak Working Memory skills often respond “I can’t remember what I read” after reading a text.

Click HERE to learn how to combat hearing this response from students by learning the Best Strategy for Teaching Reading Comprehension!

Working Memory is involved in this comprehension beginning at the word level for students. Once a word is read, its corresponding meaning is identified and held in the student’s mind. Working Memory must then be used for comprehension at the sentence level when a student is then required to keep each of those word meanings in their mind and then, link these to make meaning from the sentence. This task is repeated at the paragraph level, requiring Working Memory once again. Students with strong decoding skills, but weak Working Memory skills often respond “I can’t remember what I read” after reading a text.

Click HERE to learn how to combat hearing this response from students by learning the Best Strategy for Teaching Reading Comprehension!

|

Working Memory is involved in other literacy skills too. For example, Working Memory is used to hold and sequence sounds when a student is spelling words. Students also use their Working Memories for composing, holding, and connecting ideas when they are writing their own texts.

Therefore, Working Memory plays a crucial role in reading by supporting phonological awareness, decoding, oral reading fluency, and reading comprehension. Students with weak Working Memory skills may struggle with various aspects of reading, including identifying rhyming words, decoding unfamiliar words, and comprehending text at the word, sentence, and paragraph levels. Working Memory is also involved in other literacy skills, such as spelling and writing. Therefore, it is important for educators to assess and support students' Working Memory abilities to help them become successful readers. |

How Do You Know What a Student’s Working Memory Ability is Without Testing?

It's important to note that while these signs may indicate weak Working Memory skills, they could also be caused by other factors such as attention difficulties or processing speed deficits. It's always best to have a professional assessment to accurately identify a student's strengths and weaknesses. However, as a teacher, if you observe any of these signs, you can work to provide targeted interventions and accommodations to support the student's learning and success.

So how do you know if a student has a weak Working Memory if they have not had cognitive testing? Well, there are a few signs students with lagging Working Memory skills may exhibit in the classroom. If a teacher observes a student…

-failing to remember what was said or expected,

-failing to recall only the first step or part of an instruction or task,

-failing to remember classroom routines,

-repeating or skipping over words in a sentence,

-struggling to remember several sentences,

-unable to identify the rhyming words,

-failing to recall the sequence of events in a story,

-lacking concentration, or appearing easily distracted,

-“zoning out” on occasion,

-difficulty engaging in active listening, and/or

-offering an answer to a question but forgetting what to say when called upon,

-demonstrating start-stop performances in a task, and/or

-being unable to persevere on tasks (failing to complete tasks)

the student has weak Working Memory skills.

So how do you know if a student has a weak Working Memory if they have not had cognitive testing? Well, there are a few signs students with lagging Working Memory skills may exhibit in the classroom. If a teacher observes a student…

-failing to remember what was said or expected,

-failing to recall only the first step or part of an instruction or task,

-failing to remember classroom routines,

-repeating or skipping over words in a sentence,

-struggling to remember several sentences,

-unable to identify the rhyming words,

-failing to recall the sequence of events in a story,

-lacking concentration, or appearing easily distracted,

-“zoning out” on occasion,

-difficulty engaging in active listening, and/or

-offering an answer to a question but forgetting what to say when called upon,

-demonstrating start-stop performances in a task, and/or

-being unable to persevere on tasks (failing to complete tasks)

the student has weak Working Memory skills.

How can we support Working Memory in the classroom?

Working Memory has always been generally considered to be a constant trait and not easily improved through intervention, but there is some debate about this.

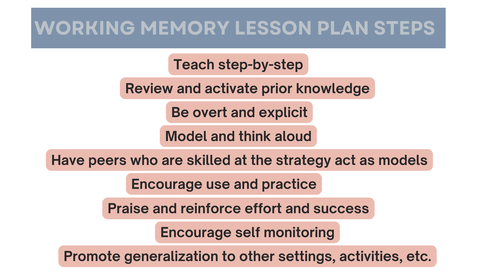

So until this debate gets resolved, the best way teachers can support Working Memory in the classroom is by making changes to the learning environment to support a student’s lagging skills. By combining classroom accommodations with Working Memory Lesson Plans, teachers can help students increase their ability to hold information briefly in their mind and process it.

Classroom accommodations for Working Memory increase students’ efficiency and functioning.

The following are Working Memory Classroom Accommodations:

SETTING Accommodations (These accommodations focus on a change in the student’s environment)

Integrate Movement

One of the easiest ways to activate students’ Working Memory skills is with physical activity. Studies have shown that physical activity has a positive impact on emotional regulation, mood, sleep, and concentration. By adding movement, before, during, and after learning, we can help students create a level of alertness needed to focus and concentrate. So think about adding some yoga sequences (get some yoga sequences HERE) before instruction and during transitions. Within your instruction, you might add movement with stations or acting out vocabulary words.

As a general rule of thumb for planning, students’ attention spans are about two to three minutes per year of age on average (Boise, 2022). This means that kindergartners can hold attention for about 10 and 18 minutes long, and the average attention span of a third grader is about 16 and 27 minutes.

So by embedding movement into the instruction, you aren’t interrupting student learning, but you are allowing students’ Working Memory to stay engaged. But when they need a brain break, you can…

Incorporate Mindfulness

Mindfulness is a way of helping students be present in each moment, noticing what they are experiencing—with compassion and without judgment. Studies have shown that mindfulness and mediation are linked to Working Memory. Multiple studies show that learning basic mindfulness techniques can improve students’ attention span and focus, concentration and engagement, decision-making skills, and help them more easily recall information. It has also been shown to improve sleep, compassion, and self esteem.

Teach your students breathing techniques like Starfish Breathing and begin having a common emotional classroom language...

“Let’s stop and take a breath.”

“Let’s all regulate our bodies with some Starfish Breathing.”

“Do you need to re-regulate yourself and access the calming corner?” (get Calming Corner resources HERE)

“Let’s focus our attention with our Glitter Jars.” (get a Glitter Jar resource HERE)

to address student stress and anxiety.

Calm, a mindfulness meditation website and app of classroom mindfulness activities, offers free annual subscriptions for teachers (get it HERE).

So until this debate gets resolved, the best way teachers can support Working Memory in the classroom is by making changes to the learning environment to support a student’s lagging skills. By combining classroom accommodations with Working Memory Lesson Plans, teachers can help students increase their ability to hold information briefly in their mind and process it.

Classroom accommodations for Working Memory increase students’ efficiency and functioning.

The following are Working Memory Classroom Accommodations:

SETTING Accommodations (These accommodations focus on a change in the student’s environment)

Integrate Movement

One of the easiest ways to activate students’ Working Memory skills is with physical activity. Studies have shown that physical activity has a positive impact on emotional regulation, mood, sleep, and concentration. By adding movement, before, during, and after learning, we can help students create a level of alertness needed to focus and concentrate. So think about adding some yoga sequences (get some yoga sequences HERE) before instruction and during transitions. Within your instruction, you might add movement with stations or acting out vocabulary words.

As a general rule of thumb for planning, students’ attention spans are about two to three minutes per year of age on average (Boise, 2022). This means that kindergartners can hold attention for about 10 and 18 minutes long, and the average attention span of a third grader is about 16 and 27 minutes.

So by embedding movement into the instruction, you aren’t interrupting student learning, but you are allowing students’ Working Memory to stay engaged. But when they need a brain break, you can…

Incorporate Mindfulness

Mindfulness is a way of helping students be present in each moment, noticing what they are experiencing—with compassion and without judgment. Studies have shown that mindfulness and mediation are linked to Working Memory. Multiple studies show that learning basic mindfulness techniques can improve students’ attention span and focus, concentration and engagement, decision-making skills, and help them more easily recall information. It has also been shown to improve sleep, compassion, and self esteem.

Teach your students breathing techniques like Starfish Breathing and begin having a common emotional classroom language...

“Let’s stop and take a breath.”

“Let’s all regulate our bodies with some Starfish Breathing.”

“Do you need to re-regulate yourself and access the calming corner?” (get Calming Corner resources HERE)

“Let’s focus our attention with our Glitter Jars.” (get a Glitter Jar resource HERE)

to address student stress and anxiety.

Calm, a mindfulness meditation website and app of classroom mindfulness activities, offers free annual subscriptions for teachers (get it HERE).

|

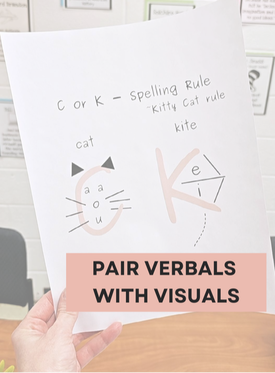

PRESENTATION Accommodations (These accommodations focus on how the information will be provided to the student)

While we have our students’ attention, it’s our job to help them move the information we are teaching them into their Working Memory. And here’s what we know about that… -When information is presented orally, students retain 10% of that information three days later, but… -When information is presented orally AND paired with a powerful image, students retain 65% of that information three days later (Medina, 2008). Sooo… Pair classroom verbals with visuals. |

Most classroom tasks require processing of verbal and visual information. Pairing verbals with visuals in the classroom creates high-quality representations of new information for students, and this facilitates learning by solidifying the ‘what’ of the lesson. It does this because by presenting complementary verbal and visual information, we are helping to reduce the load on students’ Working Memories.

Think about it. When someone talks too much or too fast, it’s difficult to concentrate and comprehend. When too much visual information comes at you too fast at once, you feel overloaded. In both of these scenarios, one of the brain networks gets overloaded, and as a result, we experience a Working Memory burnout.

Pairing verbals with visuals enhances memory of presented information. To support students with weak Working Memory skills, we can provide teacher-prepared handouts, copies of class notes, completed graphic organizers, etc. Having this information allows students with weak Working Memories to identify the salient information and to correctly organize the information for understanding. Both of these activities enhance memory of the information as well.

Think about it. When someone talks too much or too fast, it’s difficult to concentrate and comprehend. When too much visual information comes at you too fast at once, you feel overloaded. In both of these scenarios, one of the brain networks gets overloaded, and as a result, we experience a Working Memory burnout.

Pairing verbals with visuals enhances memory of presented information. To support students with weak Working Memory skills, we can provide teacher-prepared handouts, copies of class notes, completed graphic organizers, etc. Having this information allows students with weak Working Memories to identify the salient information and to correctly organize the information for understanding. Both of these activities enhance memory of the information as well.

|

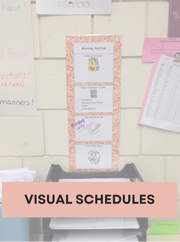

Some other ways we see verbals paired with visuals in the classroom might include…

-a classroom schedule that is written out and paired with visuals corresponding to each activity. -verbal instructions being reinforced with visuals, gestures and active demonstrations -directions for an activity written out on the board with visuals next to each instruction -exemplars or examples of completed expected outcomes on assignments (i.e. sample writing piece, model) |

Connecting information, both verbally and visually, helps students to code information in their brains in different ways. And pairing verbals with visuals allows the Working Memory load to be shared across the brain’s processors instead of being concentrated to any one network.

Reduce Students’ Cognitive Load (Chunk Information and Distribute Practice)

Studies have shown that we are generally able to hold onto about seven bits of information at a time; however, these studies are based upon adults. Students are typically able to hold onto fewer bits of information than that. And when we are not cognizant of this, we can overload our students’ Working Memories. An overloaded Working Memory can lead to fatigue and frustration.

So how do we avoid overloading our students?

We can reduce the students’ cognitive load. When Working Memory is needed for a learning task, we can work to reduce any other cognitive processes that are required during that task so that the student can focus on learning the skill. We can do this by taking a multi-step approach to supporting students with working memory deficits (Gathercole & Alloway., 2010).

Reduce Students’ Cognitive Load (Chunk Information and Distribute Practice)

Studies have shown that we are generally able to hold onto about seven bits of information at a time; however, these studies are based upon adults. Students are typically able to hold onto fewer bits of information than that. And when we are not cognizant of this, we can overload our students’ Working Memories. An overloaded Working Memory can lead to fatigue and frustration.

So how do we avoid overloading our students?

We can reduce the students’ cognitive load. When Working Memory is needed for a learning task, we can work to reduce any other cognitive processes that are required during that task so that the student can focus on learning the skill. We can do this by taking a multi-step approach to supporting students with working memory deficits (Gathercole & Alloway., 2010).

|

First, recognize what the hurdles to the curriculum are for the student. Look for signs that the student is having difficulty maintaining ideas or instructions in mind.

Second, conduct an audit of the Working Memory loads required for the learning task. For example, I’m seeing that the student is able to complete the first step in an activity, but often forgets the next steps. This is a Working Memory hurdle that I am observing. |

So I write out the steps on the board and support each step with a visual. This support can be utilized by all students to ensure that they are on track and independent in their learning. However, each time I lesson plan, I conduct my audit of the Working Memory loads required for the activity. Let’s say the activity requires many steps and lots of information to process. For such tasks, I work to reduce the complexity of the task and eliminate meaningless materials.

When we reduce the processing load for a student or decrease the amount of information that needs to be remembered, we can eliminate the hurdles to the curriculum.

Here are some ways to reduce students’ cognitive load…

1-Chunk Information: Break down tasks into small steps AND number these steps or depict them in a visual checklist so students can track their progress.

Researchers suggest that Working Memory times out after 5 to 10 minutes for preadolescents and 10 to 20 minutes for adults (Souza, 2011). Therefore, chunking information into shorter segments and providing opportunities for processing in between is a great practice for the classroom.

Chunking can also be a strategy that can be applied to oral reading fluency. We can teach students to read sentences in meaningful chunks. By chunking a sentence, we can help students read quicker to support comprehension and reduce the number of parts to be stored in Working Memory for immediate processing.

Not only can we chunk information for students, we can chunk their learning too.

2-Distribute Practice: Distributed practice is a learning technique where practice occurs in multiple short sessions over a long period of time, with an acceptable amount of space between each session. Research purports that when learning is spaced out, rather than presented all in one long session, memory is better supported.

Think about cramming for a test. Breaking up the study sessions into smaller chunks of time is more effective than cramming everything you need to know in a 2 hours study session.

Distributed Practice helps students remember new information and generalize it (Vlach, Ankowski, & Sandhofer, 2012). It also gives students time to process and clarify newly learned concepts through questioning, without overloading the Working Memory demands needed for this learning. This is because when we distribute practice, we prevent cognitive overload; thus improving memory!

We can work to support both of these practices for reduction of the cognitive load by implementing the following accommodations:

-Frequently check-in with students for understanding

-Allow for notetaking and voice recording to support recall of the steps needed to complete an activity or of the most salient points of a lecture. Or we can also teach students to use Post-Its to jot information down. This can be helpful for remembering directions. Similarly, we can teach students with decreased Working Memory skills to make lists and/or write down the steps in a project, routine, etc.

- Use simplistic, concrete language. It’s helpful to shorten what you say, speak at a slower pace, and use less complex sentences so the student is able to focus on the most notable points of the instruction.

-Make sure that you have the student’s attention before an instruction is delivered - and emphasize what the student should be listening for!

-Use prompts to support the student’s memory of the task and how to access supports for their learning. “What is the question asking you to do?” “What’s the first step?” “What do you need to do next?” “Where can I find the next step in the directions?”

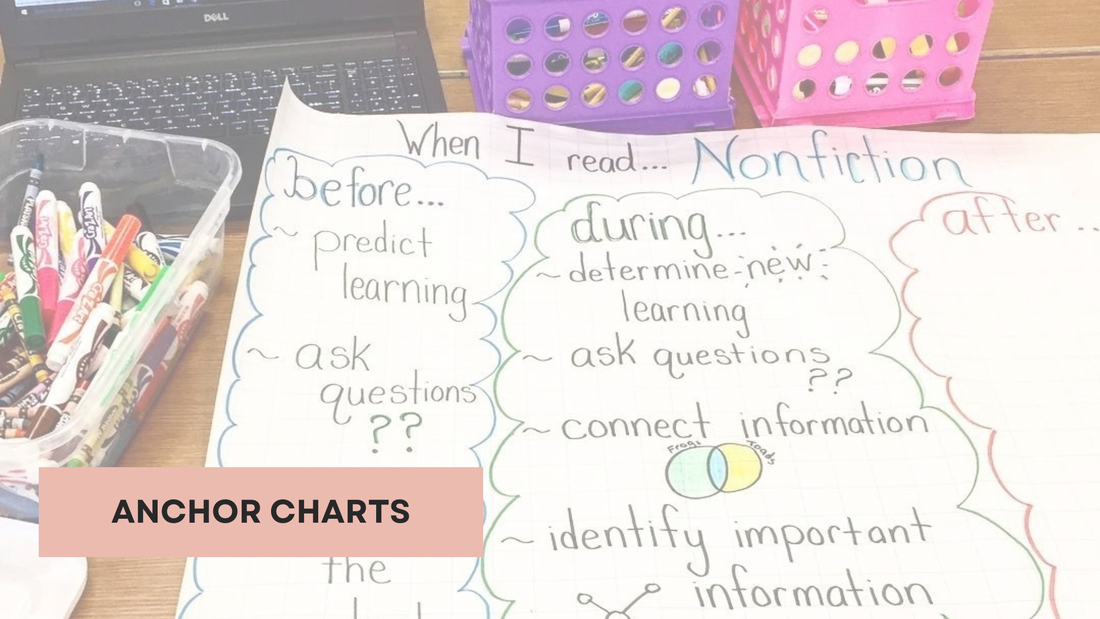

Repetition is another classroom accommodation that supports the way we present information to our students. Through repetition, we are able to repeat information and emphasize the important information.

Typical students should only require a few repetitions for learning. They are able to hear the information, and then, shift to applying it to learning tasks. Students with lagging Working Memory skills, however, require more repetition to retain information. For example, in one study, it was found that students with learning disabilities learned new words better after hearing it at least 36 times compared to 12 or 24 times in typically developing children (Storkel et al., 2017). Therefore, if we make a conscious effort to use repetition in our classrooms by providing students with review and repetition of new information and repetition of task instructions, keywords, or comprehension checks, we bolster the learning of all students. Repetition allows information to become more familiar, and this offsets demands place on students’ Working Memory once more complex tasks are introduced. Students can then be more successful in applying newly learned information to learning tasks.

Memory aids are tools that allow for on-going repetition of skills and are also able to emphasize the important information for students. Anchor charts, student reference notebooks, personalized word walls, spelling rule charts, and success criteria (i.e. Did-I? checklist) are some examples that work to reduce the extraneous load and allow students to access guiding information without having to search long term memory.

When we reduce the processing load for a student or decrease the amount of information that needs to be remembered, we can eliminate the hurdles to the curriculum.

Here are some ways to reduce students’ cognitive load…

1-Chunk Information: Break down tasks into small steps AND number these steps or depict them in a visual checklist so students can track their progress.

Researchers suggest that Working Memory times out after 5 to 10 minutes for preadolescents and 10 to 20 minutes for adults (Souza, 2011). Therefore, chunking information into shorter segments and providing opportunities for processing in between is a great practice for the classroom.

Chunking can also be a strategy that can be applied to oral reading fluency. We can teach students to read sentences in meaningful chunks. By chunking a sentence, we can help students read quicker to support comprehension and reduce the number of parts to be stored in Working Memory for immediate processing.

Not only can we chunk information for students, we can chunk their learning too.

2-Distribute Practice: Distributed practice is a learning technique where practice occurs in multiple short sessions over a long period of time, with an acceptable amount of space between each session. Research purports that when learning is spaced out, rather than presented all in one long session, memory is better supported.

Think about cramming for a test. Breaking up the study sessions into smaller chunks of time is more effective than cramming everything you need to know in a 2 hours study session.

Distributed Practice helps students remember new information and generalize it (Vlach, Ankowski, & Sandhofer, 2012). It also gives students time to process and clarify newly learned concepts through questioning, without overloading the Working Memory demands needed for this learning. This is because when we distribute practice, we prevent cognitive overload; thus improving memory!

We can work to support both of these practices for reduction of the cognitive load by implementing the following accommodations:

-Frequently check-in with students for understanding

-Allow for notetaking and voice recording to support recall of the steps needed to complete an activity or of the most salient points of a lecture. Or we can also teach students to use Post-Its to jot information down. This can be helpful for remembering directions. Similarly, we can teach students with decreased Working Memory skills to make lists and/or write down the steps in a project, routine, etc.

- Use simplistic, concrete language. It’s helpful to shorten what you say, speak at a slower pace, and use less complex sentences so the student is able to focus on the most notable points of the instruction.

-Make sure that you have the student’s attention before an instruction is delivered - and emphasize what the student should be listening for!

-Use prompts to support the student’s memory of the task and how to access supports for their learning. “What is the question asking you to do?” “What’s the first step?” “What do you need to do next?” “Where can I find the next step in the directions?”

Repetition is another classroom accommodation that supports the way we present information to our students. Through repetition, we are able to repeat information and emphasize the important information.

Typical students should only require a few repetitions for learning. They are able to hear the information, and then, shift to applying it to learning tasks. Students with lagging Working Memory skills, however, require more repetition to retain information. For example, in one study, it was found that students with learning disabilities learned new words better after hearing it at least 36 times compared to 12 or 24 times in typically developing children (Storkel et al., 2017). Therefore, if we make a conscious effort to use repetition in our classrooms by providing students with review and repetition of new information and repetition of task instructions, keywords, or comprehension checks, we bolster the learning of all students. Repetition allows information to become more familiar, and this offsets demands place on students’ Working Memory once more complex tasks are introduced. Students can then be more successful in applying newly learned information to learning tasks.

Memory aids are tools that allow for on-going repetition of skills and are also able to emphasize the important information for students. Anchor charts, student reference notebooks, personalized word walls, spelling rule charts, and success criteria (i.e. Did-I? checklist) are some examples that work to reduce the extraneous load and allow students to access guiding information without having to search long term memory.

Memory aids can assist students in becoming independent in accessing the content of the curriculum by eliminating demands on the Working Memory. This is because such memory aids allow a student to outsource memory requirements needed for a learning activity.

By making meaningful connections for students, and being explicit when we teach these connections to our students, is another presentation accommodation that will support students with lagging Working Memory skills. Remember, students learn better when we pair the verbal output with visuals. So we can incorporate a similar approach when making meaningful connections. This is because limitations of the Working Memory are supported when we help students mentally cluster information into larger concepts, or main ideas (Bailey & Pransky, 2014). When we create clear links for students between a new task and previous learning as a means of accessing knowledge in long-term memory (i.e. “Where/When have you seen something like this before?”), we are helping students to link information.

By making meaningful connections for students, and being explicit when we teach these connections to our students, is another presentation accommodation that will support students with lagging Working Memory skills. Remember, students learn better when we pair the verbal output with visuals. So we can incorporate a similar approach when making meaningful connections. This is because limitations of the Working Memory are supported when we help students mentally cluster information into larger concepts, or main ideas (Bailey & Pransky, 2014). When we create clear links for students between a new task and previous learning as a means of accessing knowledge in long-term memory (i.e. “Where/When have you seen something like this before?”), we are helping students to link information.

|

Graphic organizers are one example of nonlinguistic representations of information that help students make meaningful connections in their learning. Semantic mapping is another strategy for visually representing connections among concepts. A semantic word map allows students to conceptually explore their knowledge of a new word by mapping it with other related words or phrases similar in meaning to the new word. Summarizing, at the end of the lesson, helps to emphasize the important points of a lesson for students to recall (i.e. “What did we learn in this lesson?”).

|

|

And prior to a learning experience, we should prime our students’ memories! Tap into students’ background knowledge, and if they are lacking background knowledge, give them the background knowledge needed for the learning experience. Think warm-up drills like letter-sound correspondence flashcards or fluency practice that starts with words and then phrases, including those words, that students will read in a text. (Click HERE to learn more about this instructional sequence for fluency.)

|

|

And speaking of reading, teaching of phonological awareness skills has been shown to improve students’ Working Memory for reading. Phonological awareness activities that emphasize the phonological structure of a word, such as counting syllables or identifying sounds, has been demonstrated to improve long-term memory of the sound structure of words (or their phonological representations) for reading and for spelling.

RESPONSE Accommodations (These accommodations focus on how the student will provide information) Help the student to self-advocate. It can be upsetting for a student to lose instructions in the middle of a task, but students who have poor Working Memory skills can learn to respond to this through development of self advocacy skills. Asking for help or clarification on directions, learning to take notes, organize materials, and make lists allows students to take control of their learning and self advocate to get what they need. |

TIMING/SCHEDULING Accommodations (These accommodations focus on altering time allocations or the schedule, such as a specific time of day, extra time, etc.)

One of the most common accommodations for students with poor Working Memory skills is to allow for extended or untimed learning tasks. This should be used for tasks and assessments where speed is not relevant to the outcome. For example, in measures of word reading fluency, a student should be timed, but for a written response to a text, time should not have an influence on the outcome so allow for it to be untimed!

Having extended and untimed assessments also alleviates the stress of time on a student who lags Working Memory skills.

But remember, we can also alleviate the cognitive load on the task of assessments as well by allowing for other accommodations like the reference charts, spelling rules notebooks, writing checklists, spelling strategy cards, and more. These are some examples of tangible tools we can offer students.

We can also teach our students invisible tools that they can learn to utilize to effectively tackle content too.

One of the most common accommodations for students with poor Working Memory skills is to allow for extended or untimed learning tasks. This should be used for tasks and assessments where speed is not relevant to the outcome. For example, in measures of word reading fluency, a student should be timed, but for a written response to a text, time should not have an influence on the outcome so allow for it to be untimed!

Having extended and untimed assessments also alleviates the stress of time on a student who lags Working Memory skills.

But remember, we can also alleviate the cognitive load on the task of assessments as well by allowing for other accommodations like the reference charts, spelling rules notebooks, writing checklists, spelling strategy cards, and more. These are some examples of tangible tools we can offer students.

We can also teach our students invisible tools that they can learn to utilize to effectively tackle content too.

|

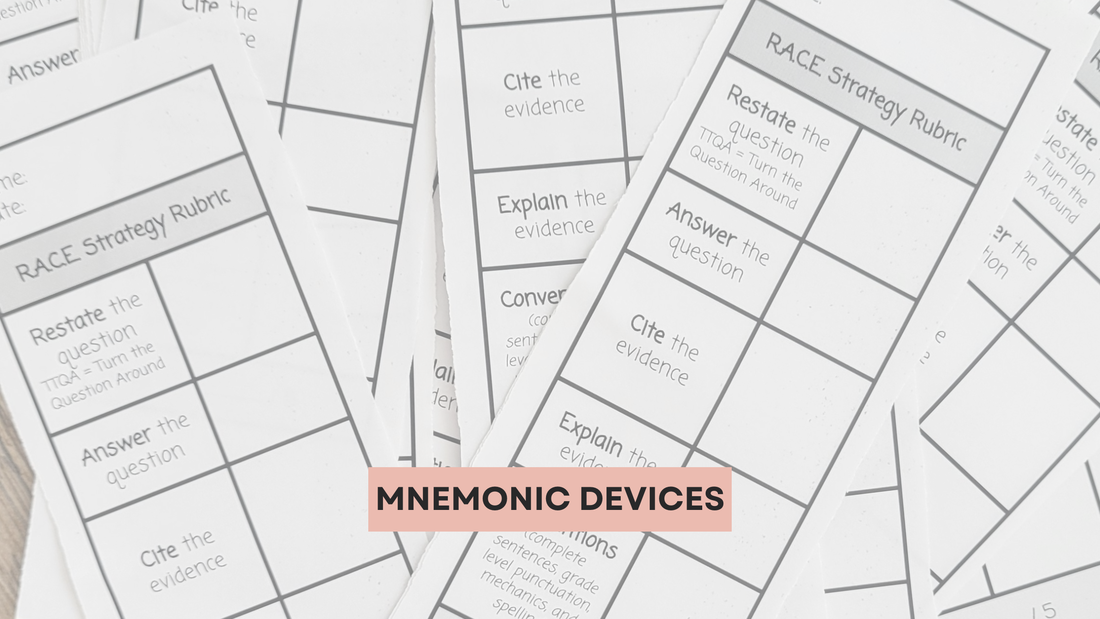

A mnemonic device is one such invisible tool. Mnemonic devices help students recall information.

RACES is a mnemonic device that stands for Restate the question, Answer the question, Cite the text, Explain, and Summarize. This strategy helps students learn how to build a strong argument and can be applied to such tasks as responding to a text-based fiction or nonfiction prompt or responding to an opinion prompt. It can be explicitly taught to students and applied across content areas and tasks. You can read more about how to teach the RACES tool HERE. |

|

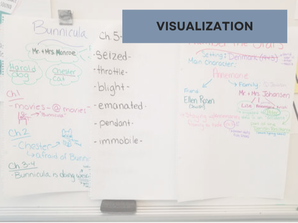

Visualization is another strategy that we can teach our students to support their Working Memory skill of recall. Students can visualize what they are reading (or listening to) to support their reading comprehension and recall of the text. We can also help students to visualize and relate it to a picture or connect it to an object or place. By making these connections, students are better able to recall information.

Click HERE to learn more about visualization. |

We can teach our students how to use Working Memory supports through Working Memory Lesson Plans. Working Memory Lesson Plans involve teaching students more effective practices to store, maintain and retrieve information from Working Memory. These lessons involve teaching one strategy at a time, and then, supporting students in generalizing the strategy to many different Working Memory tasks across content areas. Teachers target a Working Memory support that applies to student learning and teach it to students.

So for example, I introduce the RACES (Restate the question, Answer the question, Cite the text, Explain, and Summarize) strategy to my students when we are learning to respond to text-based prompts in our English Language Arts block. RACES is also the tool students use in the English Language Arts block for argument writing. I re-introduce RACES when my students take the perspective of a historical figure we are learning about in Social Studies. We use the RACES strategy in Science when writing about our laboratory experiment findings. In Mathematics, students can use the DICE strategy to solve a word problem and then, the RACES strategy to write about how they solved the problem.

Working Memory Lesson Plans help students improve their concentration to detail, stay attentive to it while processing information efficiently, and use accommodations like student reference notebooks, mnemonic devices, visualization, etc. - to effectively access the curriculum.

And Teachers can purchase Working Memory activity books or get activities on TPT that target these skills, when the time crunch of the classroom impacts being able to deliver Working Memory lessons.

So for example, I introduce the RACES (Restate the question, Answer the question, Cite the text, Explain, and Summarize) strategy to my students when we are learning to respond to text-based prompts in our English Language Arts block. RACES is also the tool students use in the English Language Arts block for argument writing. I re-introduce RACES when my students take the perspective of a historical figure we are learning about in Social Studies. We use the RACES strategy in Science when writing about our laboratory experiment findings. In Mathematics, students can use the DICE strategy to solve a word problem and then, the RACES strategy to write about how they solved the problem.

Working Memory Lesson Plans help students improve their concentration to detail, stay attentive to it while processing information efficiently, and use accommodations like student reference notebooks, mnemonic devices, visualization, etc. - to effectively access the curriculum.

And Teachers can purchase Working Memory activity books or get activities on TPT that target these skills, when the time crunch of the classroom impacts being able to deliver Working Memory lessons.

How can teachers support Working Memory in Reading?

|

Students’ Working Memory skills play a critical role in reading words and comprehending connected words in text. Teachers can teach students how to tackle text by teaching them to be active readers. Teach your students to underline, highlight, or jot key words down in the margin when reading a text. To consolidate this information and move it into long-term memory, students can then make outlines or use graphic organizers.

The Structured Literacy approach to reading is informed by knowledge of oral and written language and how it is learned. It focuses on the reciprocal skills of reading and writing. |

And it supports weak Working Memory skills because it is direct, explicit, systematic, structured, sequential, cumulative, multisensory, diagnostic, and responsive. Structured Literacy prepares students to decode words in an explicit and systematic manner by explicitly teaching students the rules, concepts and patterns.

You can read more about the Structured Literacy approach HERE.

You can read more about the Structured Literacy approach HERE.

How can teachers support Working Memory skills in Students with Learning Disabilities?

Losing information stored in their working memory can be a hurdle to student learning so we can remove those hurdles to the curriculum through a Structured Literacy approach to reading, strategy training and classroom accommodations. But even with this, there may be a small handful of students who continue to struggle or who need more.

Poor working memory affects approximately 15% of students, but it is estimated that approximately 70% of students with Learning Disabilities in reading score very low on working memory assessments (Holmes, et al., 2010; Gathercole & Alloway, 2008). This percentage is significant in comparison to students who do not have learning disabilities. So as a result, students with Learning Disabilities may find the academic environment particularly challenging, due primarily to Working Memory deficits (Gathercole & Alloway, 2008; Dehn, 2008).

So how can teachers help support Working Memory skills in Students with Learning Disabilities?

Provide all of the supports we have previously mentioned AND intervention! A careful, meta-analytic review, concluded that "...there is good evidence that difficulties with word reading and problems with reading and language comprehension can be improved by intensive, targeted educational interventions" (Melby-Lervag, et al., 2016).

The earlier students receive intervention the better! And during intervention, it is important to focus on both repetitive practice (think letter-sound drills) to help increase automaticity AND flood students with language opportunities within meaningful contexts.

Click HERE to get a 5 Step Reading Lesson Plan grounded in the Science of Reading to support ALL students

Poor working memory affects approximately 15% of students, but it is estimated that approximately 70% of students with Learning Disabilities in reading score very low on working memory assessments (Holmes, et al., 2010; Gathercole & Alloway, 2008). This percentage is significant in comparison to students who do not have learning disabilities. So as a result, students with Learning Disabilities may find the academic environment particularly challenging, due primarily to Working Memory deficits (Gathercole & Alloway, 2008; Dehn, 2008).

So how can teachers help support Working Memory skills in Students with Learning Disabilities?

Provide all of the supports we have previously mentioned AND intervention! A careful, meta-analytic review, concluded that "...there is good evidence that difficulties with word reading and problems with reading and language comprehension can be improved by intensive, targeted educational interventions" (Melby-Lervag, et al., 2016).

The earlier students receive intervention the better! And during intervention, it is important to focus on both repetitive practice (think letter-sound drills) to help increase automaticity AND flood students with language opportunities within meaningful contexts.

Click HERE to get a 5 Step Reading Lesson Plan grounded in the Science of Reading to support ALL students

Overlearning has also been identified as an effective practice for students with Learning Disabilities. Overlearning is a strategy of repeated practice with a skill to strengthen a student’s memory and performance of and with that skill. Repeated practice beyond the initial learning phase enhances performance because the neural processes involved in the repeated practice become more efficient with the skill being learned. And when this happens students’ recall speed improves.

Overlearning can be used until a student has acquired a skill beyond mastery and at mastery begins to demonstrate several error-free repetitions. Several error-free repetitions are required to solidify the information in a student’s long-term memory.

By implementing many of these Working Memory strategies, we are supporting the principles of the Universal design for learning (UDL) teaching approach. UDL works to accommodate the needs and abilities of all learners and eliminates unnecessary hurdles in the learning process. But when we are implementing specially designed instruction to support students with Learning Disabilities with weak Working Memory skills, we may need to write IEP goals to develop Working Memory skills.

Overlearning can be used until a student has acquired a skill beyond mastery and at mastery begins to demonstrate several error-free repetitions. Several error-free repetitions are required to solidify the information in a student’s long-term memory.

By implementing many of these Working Memory strategies, we are supporting the principles of the Universal design for learning (UDL) teaching approach. UDL works to accommodate the needs and abilities of all learners and eliminates unnecessary hurdles in the learning process. But when we are implementing specially designed instruction to support students with Learning Disabilities with weak Working Memory skills, we may need to write IEP goals to develop Working Memory skills.

What are IEP goals for Working Memory?

And for those Special Education students who need more, we may need to write IEP goals!

Click HERE to learn how to choose IEP goal areas and HERE to learn how to write IEP goals!

Use a student’s baseline performance (or current level of performance) with the identified Working Memory skill to write an IEP goal for your student.

Through our work with students, teachers can identify the areas that need improvement in each of our students. So identify students’ lagging Working Memory skills and set measurable goals that you will help the student achieve!

Click HERE to learn how to choose IEP goal areas and HERE to learn how to write IEP goals!

Use a student’s baseline performance (or current level of performance) with the identified Working Memory skill to write an IEP goal for your student.

Through our work with students, teachers can identify the areas that need improvement in each of our students. So identify students’ lagging Working Memory skills and set measurable goals that you will help the student achieve!

Working Memory IEP Goals:

1-STUDENT will accurately repeat verbal instructions with 80% accuracy before beginning assignment in 4 out of 5 opportunities as evidenced by teacher/staff observation data.

2-STUDENT will independently utilize a provided (and taught) reference tool (i.e. student notebook, reference chart, etc.) to access content material in 4 out of 5 opportunities as evidenced by teacher/staff observation data.

3-STUDENT will accurately follow classroom routines/procedures for XXX (i.e. entering the classroom, turning in work, packing up, etc.) with 80% accuracy in 4 out of 5 opportunities as evidenced by teacher/staff observation data.

4-STUDENT will use a given memory aid (be specific) to support memorization (and/or access) of content material with 80% accuracy in 4 out of 5 opportunities as evidenced by teacher/staff observation data.

5-STUDENT will use graphic organizers to record/recall content knowledge 8 out of 10 times as evidenced by teacher/staff observation data.

6-STUDENT will use a given assistive technology (be specific...i.e. speech to text, ipad, app, etc.) to support access of content material (or to record questions that cannot be answered immediately) in 4 out of 5 opportunities as evidenced by teacher/staff observation data.

7- STUDENT will use a written planner to keep track of assignments 100% of the time as evidenced by teacher/staff observation data.

8-STUDENT will correctly recall and sequence events in a story with 90% accuracy in 4 out of 5 opportunities as evidenced by teacher/staff data and student work samples.

9-STUDENT will understand and answer comprehension questions about a reading passage with 90% accuracy in 4 out of 5 opportunities as evidenced by student work samples.

10-STUDENT will gather information from one or more sources and apply it to a written assignment with 90% accuracy, based on a rubric in 4 out of 5 opportunities as evidenced by student work samples.

11- When given a text, STUDENT will correctly summarize the given text with 90% accuracy in 4 out of 5 opportunities as evidenced by student work samples.

2-STUDENT will independently utilize a provided (and taught) reference tool (i.e. student notebook, reference chart, etc.) to access content material in 4 out of 5 opportunities as evidenced by teacher/staff observation data.

3-STUDENT will accurately follow classroom routines/procedures for XXX (i.e. entering the classroom, turning in work, packing up, etc.) with 80% accuracy in 4 out of 5 opportunities as evidenced by teacher/staff observation data.

4-STUDENT will use a given memory aid (be specific) to support memorization (and/or access) of content material with 80% accuracy in 4 out of 5 opportunities as evidenced by teacher/staff observation data.

5-STUDENT will use graphic organizers to record/recall content knowledge 8 out of 10 times as evidenced by teacher/staff observation data.

6-STUDENT will use a given assistive technology (be specific...i.e. speech to text, ipad, app, etc.) to support access of content material (or to record questions that cannot be answered immediately) in 4 out of 5 opportunities as evidenced by teacher/staff observation data.

7- STUDENT will use a written planner to keep track of assignments 100% of the time as evidenced by teacher/staff observation data.

8-STUDENT will correctly recall and sequence events in a story with 90% accuracy in 4 out of 5 opportunities as evidenced by teacher/staff data and student work samples.

9-STUDENT will understand and answer comprehension questions about a reading passage with 90% accuracy in 4 out of 5 opportunities as evidenced by student work samples.

10-STUDENT will gather information from one or more sources and apply it to a written assignment with 90% accuracy, based on a rubric in 4 out of 5 opportunities as evidenced by student work samples.

11- When given a text, STUDENT will correctly summarize the given text with 90% accuracy in 4 out of 5 opportunities as evidenced by student work samples.

And get more Executive Functioning IEP goals HERE!

Working Memory is a necessary ability for navigating the academic environment. But when students have weak Working Memory skills, teachers can support them with the Structured Literacy approach to teaching reading, classroom accommodations, and Working Memory Lesson Plans, paired with early intervention (if necessary), students with Working Memory deficits can succeed in school!

In conclusion, Working Memory is a critical cognitive function that plays a significant role in our ability to learn and remember. As teachers, we can make a difference in supporting our students' Working Memory skills by implementing classroom accommodations and lesson plans that enhance their cognitive functioning.

So, I urge you to take action and incorporate some of the classroom accommodations and presentation strategies we discussed into your teaching practices. By doing so, you can create an environment that supports your students' Working Memory skills and helps them achieve their full potential. Let's work together to empower our students and promote their success in the classroom and beyond!

Download a FREE Working Memory Classroom Accommodations for Reading Reference Chart HERE!

Happy & Healthy Teaching!

Miss Rae

Working Memory is a necessary ability for navigating the academic environment. But when students have weak Working Memory skills, teachers can support them with the Structured Literacy approach to teaching reading, classroom accommodations, and Working Memory Lesson Plans, paired with early intervention (if necessary), students with Working Memory deficits can succeed in school!

In conclusion, Working Memory is a critical cognitive function that plays a significant role in our ability to learn and remember. As teachers, we can make a difference in supporting our students' Working Memory skills by implementing classroom accommodations and lesson plans that enhance their cognitive functioning.

So, I urge you to take action and incorporate some of the classroom accommodations and presentation strategies we discussed into your teaching practices. By doing so, you can create an environment that supports your students' Working Memory skills and helps them achieve their full potential. Let's work together to empower our students and promote their success in the classroom and beyond!

Download a FREE Working Memory Classroom Accommodations for Reading Reference Chart HERE!

Happy & Healthy Teaching!

Miss Rae

References:

Bailey, F. and Pransky, K. (2014). Memory at Work in the Classroom : Strategies to Help Underachieving Students. ASCD.

Boese, M. “Encouraging Young Children to Develop Their Attention Skills.” Edutopia. August 4, 2022. https://www.edutopia.org/article/encouraging-young-children-develop-their-attention-skills

Dehn, M. J. (2008). Working memory and academic learning: Assessment and intervention. John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Gathercole, S. E., Alloway, T. P., Kirkwood, H. J., Elliott, J. G., Holmes, J., & Hilton, K. A. (2008). Attentional and executive function behaviours in children with poor working memory. Learning and individual differences, 18(2), 214-223.

Gathercole, Susan & Alloway, Tracy. (2010). Working Memory and Learning: A Practical Guide for Teachers. SAGE Publications (CA).

Holmes, Joni & Gathercole, Susan & Dunning, Darren. (2010). Poor working memory. Advances in Child Development and Behavior - ADVAN CHILD DEVELOP BEHAV. 39. 1-43. 10.1016/B978-0-12-374748-8.00001-9.

Medina, J. (2008). Brain rules: 12 principles for surviving and thriving at work, home, and school. Seattle, WA: Pear Press

Melby-Lervåg, M., Redick, T. S., & Hulme, C. (2016). Working memory training does not improve performance on measures of intelligence or other measures of “far transfer”: Evidence from a meta-analytic review. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11(4), 512–534. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691616635612

Miyake, A., & Shah, P. (Eds.). (1999). Models of working memory: Mechanisms of active maintenance and executive control. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139174909

Souza, D. A. (2011). How the brain learns (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Storkel HL, Komesidou R, Pezold MJ, Pitt AR, Fleming KK, Romine RS. The Impact of Dose and Dose Frequency on Word Learning by Kindergarten Children With Developmental Language Disorder During Interactive Book Reading. Lang Speech Hear Serv Sch. 2019 Oct 10;50(4):518-539. doi: 10.1044/2019_LSHSS-VOIA-18-0131. Epub 2019 Oct 10. PMID: 31600474; PMCID: PMC7210430.

Vlach HA, Sandhofer CM. Distributing learning over time: the spacing effect in children's acquisition and generalization of science concepts. Child Dev. 2012 Jul-Aug;83(4):1137-44. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01781.x. Epub 2012 May 22. PMID: 22616822; PMCID: PMC3399982.

Bailey, F. and Pransky, K. (2014). Memory at Work in the Classroom : Strategies to Help Underachieving Students. ASCD.

Boese, M. “Encouraging Young Children to Develop Their Attention Skills.” Edutopia. August 4, 2022. https://www.edutopia.org/article/encouraging-young-children-develop-their-attention-skills

Dehn, M. J. (2008). Working memory and academic learning: Assessment and intervention. John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Gathercole, S. E., Alloway, T. P., Kirkwood, H. J., Elliott, J. G., Holmes, J., & Hilton, K. A. (2008). Attentional and executive function behaviours in children with poor working memory. Learning and individual differences, 18(2), 214-223.

Gathercole, Susan & Alloway, Tracy. (2010). Working Memory and Learning: A Practical Guide for Teachers. SAGE Publications (CA).

Holmes, Joni & Gathercole, Susan & Dunning, Darren. (2010). Poor working memory. Advances in Child Development and Behavior - ADVAN CHILD DEVELOP BEHAV. 39. 1-43. 10.1016/B978-0-12-374748-8.00001-9.

Medina, J. (2008). Brain rules: 12 principles for surviving and thriving at work, home, and school. Seattle, WA: Pear Press

Melby-Lervåg, M., Redick, T. S., & Hulme, C. (2016). Working memory training does not improve performance on measures of intelligence or other measures of “far transfer”: Evidence from a meta-analytic review. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11(4), 512–534. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691616635612

Miyake, A., & Shah, P. (Eds.). (1999). Models of working memory: Mechanisms of active maintenance and executive control. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139174909

Souza, D. A. (2011). How the brain learns (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Storkel HL, Komesidou R, Pezold MJ, Pitt AR, Fleming KK, Romine RS. The Impact of Dose and Dose Frequency on Word Learning by Kindergarten Children With Developmental Language Disorder During Interactive Book Reading. Lang Speech Hear Serv Sch. 2019 Oct 10;50(4):518-539. doi: 10.1044/2019_LSHSS-VOIA-18-0131. Epub 2019 Oct 10. PMID: 31600474; PMCID: PMC7210430.

Vlach HA, Sandhofer CM. Distributing learning over time: the spacing effect in children's acquisition and generalization of science concepts. Child Dev. 2012 Jul-Aug;83(4):1137-44. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01781.x. Epub 2012 May 22. PMID: 22616822; PMCID: PMC3399982.

Working Memory Classroom Accommodations for Reading Reference Chart

Learn more...

Bailey, F. and Pransky, K. (2014). Memory at Work in the Classroom : Strategies to Help Underachieving Students. ASCD.

Dawson, P., & Guare, R. (2009). Smart but scattered: The revolutionary "executive skills" approach to helping kids reach their potential. Guilford Press.

Sprenger, M. (2018). How to Teach So Students Remember. ASCD.

https://perino.pbworks.com/f/How%20To%20Teach%20So%20Students%20Remember.pdf

Dawson, P., & Guare, R. (2009). Smart but scattered: The revolutionary "executive skills" approach to helping kids reach their potential. Guilford Press.

Sprenger, M. (2018). How to Teach So Students Remember. ASCD.

https://perino.pbworks.com/f/How%20To%20Teach%20So%20Students%20Remember.pdf