700,000 English-Language Learners are identified with a learning disability, representing 14.7 percent of the total ELL population enrolled in U.S. public elementary and secondary schools in 2015. This needs to be addressed!

How do you know if an English language learner has a learning disability?

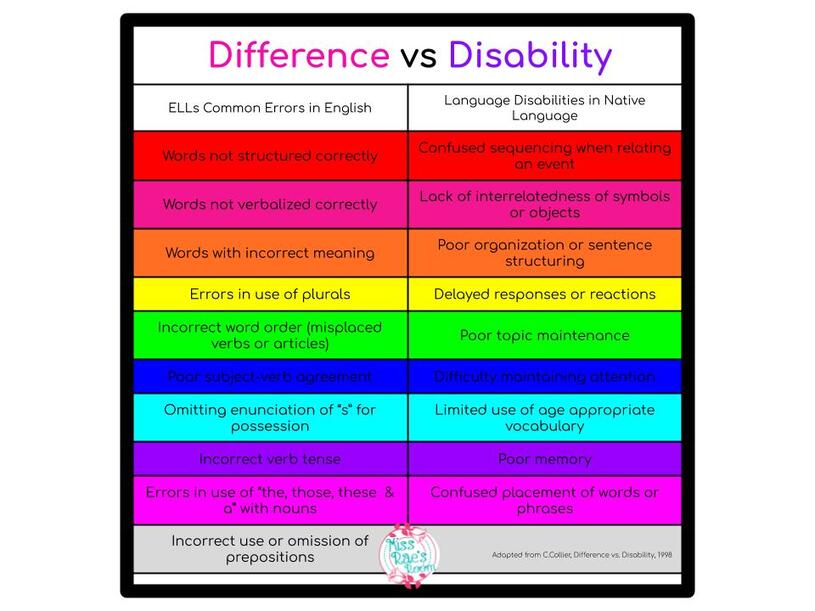

I don't know about you, but this is the big question across my state. FIRST - let's take a moment to have some real talk - ALL English language learners need to be given time - time to learn the language. Understanding the typical trajectory of second language acquisition is important for so many reasons. An understanding of learning the language is important so that we do not mis-identify our EL population as learning disabled.

But IF an ELL student’s progress is not typical, then, it's our responsibility to test.

We always start with dominance testing to establish a student’s dominant language for evaluations. Dominance testing establishes a student's level of proficiency in both languages (native and English). This is because we should ALWAYS test in a student's dominant language. Unlike their native English speaking peers, English Language students have to process the language of tests. They are also expected to comprehend cultural expectations embedded within standardized assessments. What does this mean for educators? Well, it means that for ELs, every evaluation, not given in their dominant language, becomes a test, to some degree, of language proficiency, rather than an evaluation of intellectual capacity and/or academic ability. Hence why we test in a student’s dominant language. If an EL student tested in their native language (because this was determined to be his/her dominant language) has a learning disability as indicated by the discrepancy model of standardized score comparisons, then, the student has a learning disability. A learning disability in the native language is a learning disability. But what happens when a student’s dominant language is English? How do we know this is a learning disability and not just the typical path of a second language learner? Well, we use our knowledge of the typical trajectory of second language acquisition during the evaluatory stage too! By using a simple retelling (or comprehension conversation after reading), an educator can compare this outcome (results of the comprehension conversation) with a student's expected second language acquisition trajectory. If these two match, then, this is typically indicative that the student is where he or she should be in terms of literacy. On the other hand, if these two do not correspond, a learning disability should be considered.

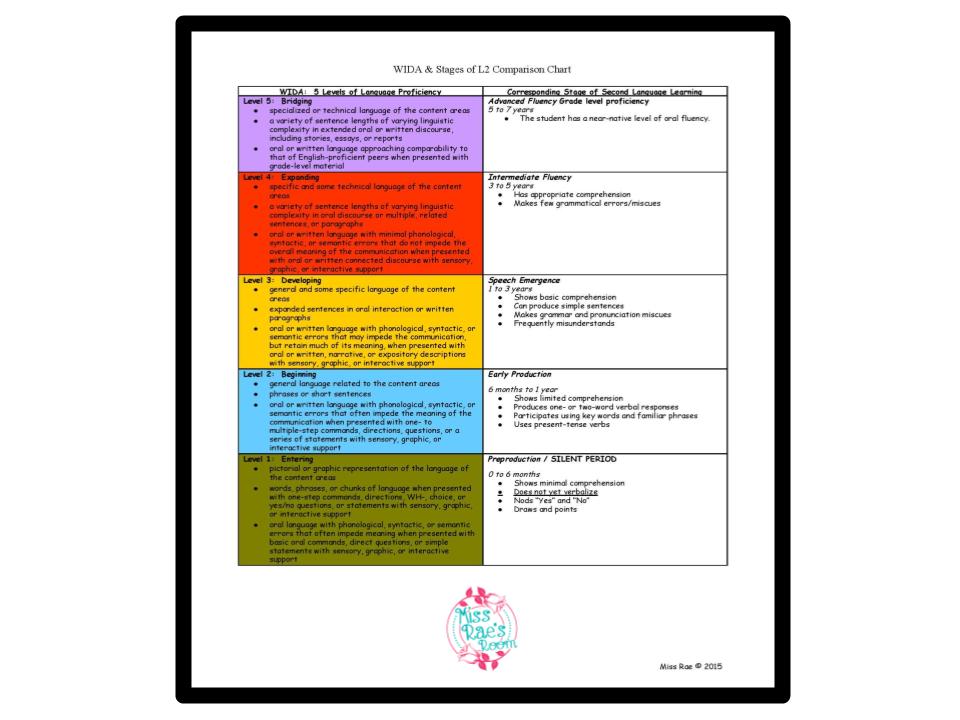

The WIDA Consortium is an educational consortium, of which 37 U.S. states participate in it. WIDA has created several screening assessments used by school systems to determine students’ English language skills and for placement of students within schools’ ELL programs.

One such assessment is called the ACCESS test. This assessment is employed annually to evaluate a student’s progress with learning English as a second language. Students receive composite scores in Oral Language, Literacy, Comprehension, and an Overall score along with four domain scores in Listening, Reading, Writing, and Speaking. These scores determine placement and drive instruction for the next school year. Here is how students may be placed based upon ACCESS scores: WIDA Level 1, Level 2 and Level 3, (ACCESS 2.0 Overall Scores 1.0-2.4) - At least two to three periods (a period is not less than 45 minutes) per day of direct ESL instruction delivered by a licensed ESL teacher WIDA Level 3, Level 4, Level 5 & Level 6 (ACCESS 2.0 Overall Scores 2.5 and higher) - At least one period (a period is not less than 45 minutes) per day of direct ESL instruction delivered by a licensed ESL teacher Most research suggests that oral proficiency takes 3 to 5 years to develop, and academic English proficiency can take 4 to 7 years. Therefore, many of our students receive ELL services while they are in school aged. So they need time, and we need to understand the trajectory of learning a second language. This trajectory along with ACCESS scores help us to determine if there is a learning disability. Ofcourse all students would benefit from additional time with a teacher, we should not mislabel or over-identify our students. This is why we use these resources. Developing a first language is automatic. Typically, children do not require explicit instruction to develop a first language. This is also true for bilingual or multilingual children who learn more than one language from birth. On the other hand, explicit teaching of a second language is required if a student is sequential bilingual, which is the definition for a student becoming bilingual by first learning one language and then another. In essence, this is considered to be a process called language learning. Unfortunately, explicit teaching of grammatical rules does not necessarily mean that a second language learner, or sequential bilingual student, will be able to speak and write with ease. Time, practice and real social experiences are needed to support the language learning process. However, listening and speaking should be simultaneous, relatively speaking, when learning a second language. This is because students are listening to the words, learning new vocabulary, and should be practicing it by speaking it. In this first stage of second language acquisition, the silent or receptive phase, second language learners dedicate time to learning vocabulary of the new language. They may also practice saying new terms. A second language learner does not produce their new language with functional fluency or comprehension (so they are not necessarily "silent" despite the name), but they are attempting speech of their new language. Early production is the second phase, and this is where students begin to build a vocabulary. Students may begin to use some terms and/or short phrases of early word combinations in their speech. This process continues through the acquisition trajectory and eventually, includes writing as well. Therefore, two scores -speaking and listening- should be relatively consistent on the ACCESS test. (Keep in mind, we are not talking about academic language. We are talking about social language. Academic language skills develop later.) However, if there is a large discrepancy between listening and speaking, there is a possibility that the child may have an expressive or receptive problem. The norm is that listening is higher that speaking - otherwise we can suspect a receptive language issues if speaking is higher than listening. If there is a language disorder in the first language, there will be a language disorder in the second language. There are of course exceptions to the rule, but essentially, high listening, low speaking with a very large discrepancy is cause for concern. We all have strengths and weaknesses within our profile. There is a typical trajectory for learning English as a second language, but there are also other factors… home life, organizational issues, attentional obstacles… these factors impact typical trajectory. But they do not indicate a learning disability. Research has suggested that the following questions should be used to determine if an ELL student’s academic struggles are the result of a learning disability or second language learning: * Is the student receiving sufficient instruction to enable him/her to make effective academic progress? *How does the student’s progress in listening, speaking, reading, and writing English as a second language compare to the expected rate of progress for his or her age and initial level of English proficiency? (Think! expected/typical second language learning trajectory) * To what extent are behaviors that might otherwise indicate a learning disability considered to be normal for the child’s cultural background or to be part of the process of U.S. acculturation? * How might additional factors—including socioeconomic status, previous educa- tion experience, fluency in his or her first language, attitude toward school, atti- tude toward learning English, and personality attributes—impact the student’s academic progress? My advice - take all factors into consideration and assess, using culturally responsive assessments that assist in fully determining a student’s needs, when determining an English Language student’s eligibility for Special Education. Our students’ futures are our responsibility. By Miss Rae Reference: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. (2018). The Condition of Education 2018 (2018-144), English Language Learners in Public Schools. Learn more by taking the course with me!

2 Comments

edith e murray

1/8/2022 12:41:35 am

I;d like to cite this article. Will that be ok? If so, what is your first and last name. Thanks.

Reply

Miss Rae

1/8/2022 08:23:51 am

Hi Edith!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

CategoriesAll 504 Academic Testing Academic Testing Reports Achievement Testing Reports Back To School B/d Reversals Coronavirus COVID-19 Discrepancy Model Distance Learning Distance Learning With LD ELL Emotional Disability Executive Functioning Extended School Year First Year Special Education Teacher Advice Fluid Reasoning FREEBIES Goal Tracking IEP IEP At A Glance IEP Goals IEP Meetings Learning Disability Oral Reading Fluency Positive Affirmations For Special Education Students Progress Monitoring Reading Remote Learning RTI Rubrics Running Records SEL For Learning Disabilities Social Emotional Learning Special Ed Teacher Interview Questions Special Ed Teacher Job Description Special Education Special Education Progress Reports Special Education Reading Special Education Reading Programs Special Education Students Special Education Teachers Special Education Teachers Positive Affirmations Special Education Teacher Tips Special Education Websites Specially Designed Reading Instruction Teaching Strategy Trauma Wilson Reading Wilson Reading IEP Goals Writer's Workshop |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed